by Bryher Scudamore

RUMMAGING through a drawer in my mother’s bureau I unearth a stash of papers, brittle with age. Tentatively, I sift through them, wondering what memories I will exhume, what secrets will unfold.

The first surprise is a poignant one: I find my parents’ marriage certificate. From it I learn that their wedding was on Christmas Eve 1947. I had no idea of the fact until then. Perhaps as children my sister and I were too involved in festive preparations – festooning the house with paper chains; waiting for Father Christmas to visit – for their anniversary to impinge on us. Or maybe it is an indication of how seldom my mother and I discussed her past that I could conjure no picture of her on her wedding day and knew nothing of how she fell in love.

My mother Peggy had died suddenly and unexpectedly of a heart attack several months earlier. The shock of losing her was so profound I fell ill with pneumonia and pleurisy and nearly died myself.

Mummy was lively, intelligent, sharp-witted and fun. She was also my mentor, my confidante and my best friend. At 75 I’d almost convinced myself she was invincible. For that reason I had never quizzed her about her life before she became a parent. Indeed, my memories of her stretched back only until I was about 10 years old.

So only when it was too late, did I realise there was a gaping chasm where my family history should be. There were so many unanswered questions; so many half-remembered childhood recollections that, without mummy’s input, would never be fleshed out.

The thought made me desolate. How could I retrieve her past? As my father had died eight years earlier, the answer seemed to lie with Betty, my mother’s best friend, who lives in California.

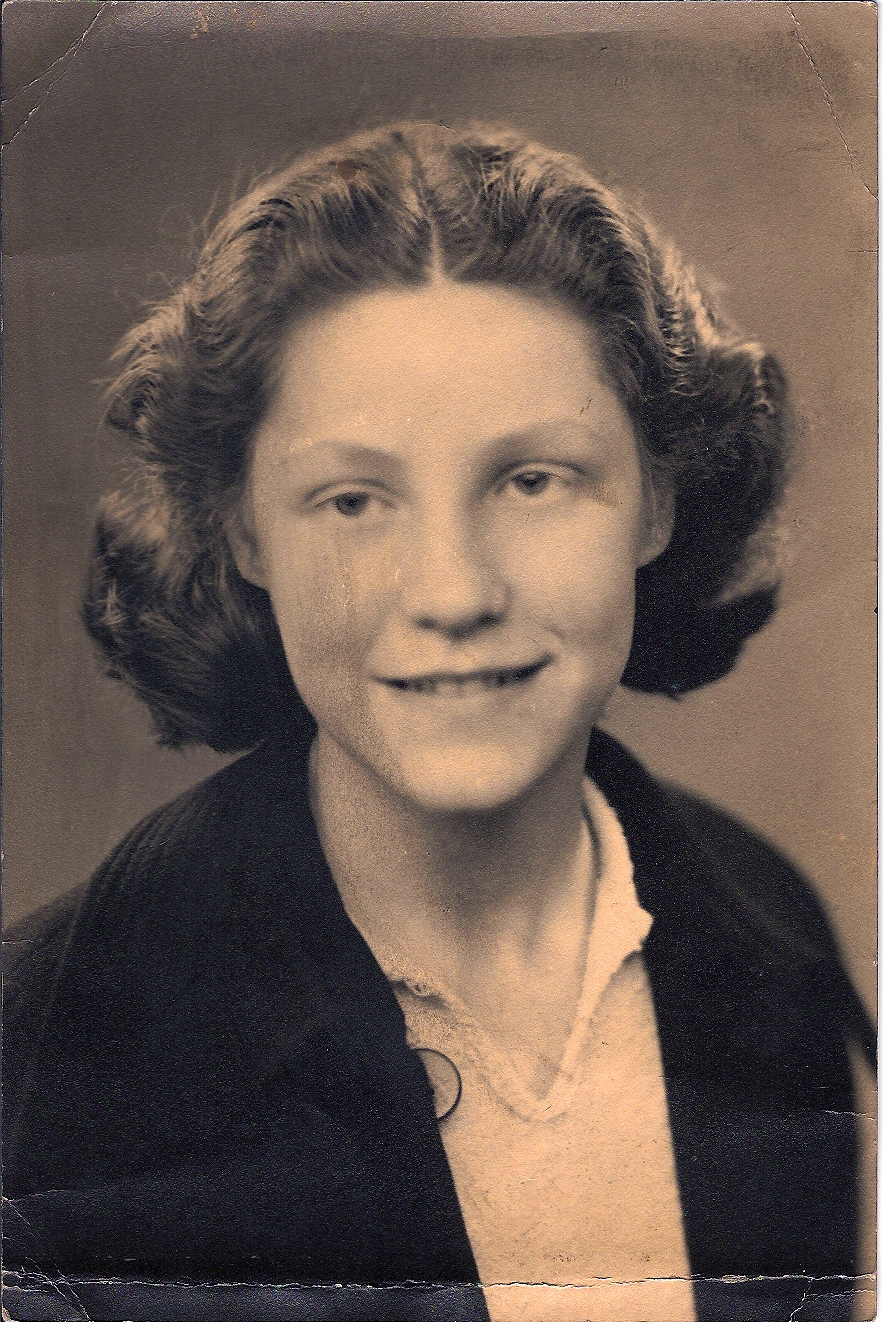

I flew out to see her, and as I knocked on her door I felt a surge of excited anticipation that was rewarded when Betty, still bright and astute, conjured up a vivid picture of mummy in her youth. She was, remembered her friend, a beauty in the Rita Hayworth mould, with a mane of copper hair, a finely chiselled jaw and high cheek bones. Although my mother retained her handsome bone structure and good looks, I had never realised she was such a striking beauty in her youth.

MY MOTHER AS SHE LOOKED WHEN I WAS BORN IN 1950

Betty recalled, too, that she had a red head’s temperament: loving and also fiery and high-spirited. This accorded with the mummy I knew in later life, who, stung by some injustice or political incompetence, would fire off a series of searing and articulate letters to the newspapers.

I had never known the story of how mummy fell in love with my father, Douglas: Betty was able to fill me in. She retained a pin-sharp memory of the day my mother had swept into Selfridges, flushed pink with excitement, to announce to Betty, who was sitting in a cubicle having her hair done, that she had met a ‘magnificent’ man at a dance. It was a coup de foudre. She knew immediately that my father was ‘the one’. He was 6’2" and slim, with dark, brooding eyes and black hair – not unlike Omar Sharif – and during the war he had been interned as a Japanese POW. Douglas, a former public school boy, was dashingly handsome and charming. I envisaged the moment of mummy’s revelation. Betty brought it to life for me and I felt a rush of emotion. A tear blurred my eye.

A PICTURE OF MY MOTHER THAT WAS TREASURED BY MY FATHER

My father and mother had been besotted with each other when they set up home in Cornwall after their wedding, buying three adjacent derelict cottages for just £52 in 1947. My paternal grandfather, who owned a prospering glass and china import business, helped to fund the purchase. Restoration work was funded by Daddy’s erratic income as an antiques dealer. So, long before the idea became fashionable, my parents had their own grand designs: they renovated the ramshackle dwellings while lodging with an acerbic and disapproving landlady.

Betty conjured a picture of her, and of my parents’ bohemian lifestyle: mummy, as well as my father, smoked tobacco in a clay pipe and visited the local pub in an era when respectable women were not expected to drink in public bars.

I never remembered my mother as a smoker, although apparently she preserved a 40-a-day habit until 1959, when she read an article linking tobacco to cancer and instantly she stopped.

And while she retained an informed interest in current affairs, I had not realised that, as a young married woman, she was also a political activist. My parents’ coterie was, in fact, both politically-aware and literary. They were friends with Daphne du Maurier, who lived near them in Fowey, and Betty remembered how they formed a Cornish Cabinet to discuss political strategy for the region.

I thought then, as a new picture of mummy began to emerge, how sad it is that we so often view our mothers merely in their parental role: as nurturers when we are children; to be defied as teenagers. Then, even when we are adults ourselves, we fail to see them as sexual, political, autonomous beings and as a result – although we adore them – we do not know them as fully-rounded people.

But I supplemented Betty’s reminiscences with my own research. And as I leafed through my mother’s diaries – which were actually little more than appointment books – I unearthed more tantalising snippets of information. Mummy mentioned in an entry during the summer of 1952 that I had played in the sand with Daphne du Maurier’s son, Kits Browning. I was two years old at the time and I knew nothing about this infant friendship until I read my mother’s diaries. But they revealed it: Kits and I had played in the sand together at Readymoney Cove as toddlers.

And by extraordinary coincidence, 46 years later, I became friends with Kits all over again. Neither of us knew we’d been infant companions –– but when my husband Paul, 62, a travel editor, and I bought a house in Bodinnick-by-Fowey in 1998 we met Daphne’s son and formed a friendship anew.

In 1955, when I was five, we had moved back to London, because, idyllic though Cornwall was, daddy’s antique business was ailing. My parents bought a rambling early Victorian house in a private road in Upper Norwood that remained the family home until mummy died.

She loved to paint in the bright back room with its French windows opening onto the garden and her work now adorns my walls. She was also a talented writer. Indeed, for many years she earned her living as a journalist, first on local papers then as managing editor of the WI journal Home and Country.

But I had no idea, until I leafed through the papers in her bureau that day in her ‘painting room’ that she had also begun writing a play, a domestic comedy, that was filed alongside the opening chapters of a thriller (she adored a good detective story). Their existence was a complete surprise. I have no clue as to when mummy began writing the play, but the thriller dates from the late 1980s. Doubtless had she lived longer, she would have finished them and tried to have them published.

The fact that my mother was an accomplished writer was, of course, no surprise to me. Her career in journalism, which she had begun when I was 10-years-old, testified to that. The revelation was that mummy had achieved so much with so little formal education.

It was Betty who told me that while she had passed the exam to go to grammar school, mummy had failed it. Her achievements, I then realised, were all the more remarkable because her education had been scant and her upbringing, impoverished.

I assume she left school at 14 with no qualifications. Certainly, for a while, my mother had shunned Betty, fearing she would look down on her because she had not graduated to grammar school. But soon there was a rapprochement and they revived their lifelong friendship.

MY MOTHER AGED 14

Betty painted a vivid visual picture of the two of them, their eye make-up improvised from charcoal because of wartime rationing, chatting animatedly as they walked from their girlhood homes in Gospel Oak, north London to the theatre in the West End. There they would see a play, a musical or operetta: Mummy adored Gilbert and Sullivan and Noel Coward. She also preserved a life-long love of Shakespeare.

Mummy had told me nothing about her early adulthood and very little about her childhood, although I knew it had been tough and that she clashed with her mother. Then I found a story she had written. It was on yellowing paper and typed on a very old fashioned typewriter. It told of jumble sales held at the Methodist Hall where her adored father was the caretaker. She described how, as a child of seven or eight, she would sneak into the hall before it opened and try on hats with magnificent feathers, or teeter on high heels, only to tear them off and put them back when the doors opened and the sale began.

So this is how, little-by-little, I got to know mummy after she died. Only posthumously did she become a three-dimensional character. When she was alive we lived in the present. I had not realised how compelling, once she died, would be the urge to find out about her past.

For this reason, when the raw grief of bereavement had abated, I made two life-changing decisions. First I decided, with my husband’s blessing, to buy my childhood home and move back there.

And as Paul and I restore the dilapidated Grade 2 listed end-of-terrace to its former glory, my memories return in sharp focus. I recollect the chill of winter mornings when I lugged a paraffin heater upstairs to the icy bathroom. I visualise frost-etched fronds on the inside of the window in my teenage bedroom at the top of the house, and remember dressing under the bedcovers so I didn’t freeze with cold.

And I sit at the beautiful walnut table around which we ate and chatted as a family. Most of all, I feel my mother is near. I know too, she would be proud of the new business she inspired me to set up.

Although I have no children of my own, I wanted to help other people keep the memory of their loved ones alive. So I gave up my job as Director of Communications at the Eden Project in Cornwall and set up autodotbiography.com. It aims to help anyone – even the least confident writer– to write their own life story, using the virtual ghost writer that I have created turns their words and pictures into a professionally-written hardback book that can be handed down through the generations.

And as I work in my office – once the bedroom my sister and I shared as children – I sense my mother’s presence at my shoulder. I feel she is guiding me. Actually I think she is smiling.

MY BELOVED MOTHER WHO INSPIRED ME TO CREATE AUTODOTBIOGRAPHY - ONE OF THE RARE PICTURES OF US TOGETHER.